Are Vaccines Effective?

Are Vaccines Effective?

It’s easy to take the protection offered by routine vaccines for granted, but in reality routine vaccines have saved over 1 million lives in the United States in the last 30 years.

Here, we address some of the most common questions about how effective vaccines are, and why they’re so important for our collective wellbeing.

This page has been verified for accuracy by a member of VYF’s Committee of Scientific and Medical Advisors, last updated February 2024.

The Germ-Fighters In Our Corner

It’s easy to take the protection offered by vaccines for granted, but vaccines have been quietly saving lives and defeating infectious diseases that used to sicken and kill many people every year.

Many of us have not seen, heard of, or experienced many of the vaccine-preventable diseases, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t still out there. Countries all over the world experience outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, and due to easy travel from country to country, diseases can be brought into unsuspecting communities across the world, including communities in the U.S.

Due to vaccines and community immunity, if there is an outbreak of disease, then it won’t get far. When most of the community is immune to a disease, then the disease cannot pass around and make people sick. However, should many people in a community decide not to get vaccinated or vaccinate their children, then an outbreak can occur, and many people could get sick.

The only vaccine-preventable disease that is completely eradicated (gone) from the world is smallpox. Polio is close to being eliminated, but still exists in several countries.

When traveling outside the U.S., check which vaccines are needed for travel to that country. It’s important to make sure you are vaccinated with enough time to make gain immunity before leaving the country, so plan accordingly. You can also check for any local outbreaks occurring in the area you are traveling to.

There are outbreaks of relatively uncommon diseases like measles in communities across the U.S. every year and if vaccination rates drop even slightly, it will only get worse. Get vaccinated before an outbreak occurs for protection from disease. Follow CDC’s recommended vaccine schedules for appropriate timing of vaccinations.

Read the stories from families who experienced vaccine-preventable diseases.

Resources:

- Vaccinate Your Family: Vaccine Benefits

- Vaccinate Your Family: Vaccines Protect Communities

- CDC: Diseases You Almost Forgot About (Thanks to Vaccines)

- CDC: Traveler’s Health

- CDC: Measles Cases and Outbreaks

- CDC Public Health Matters Blog: Measles Linked to Disneyland

Children are exposed to diseases everywhere they go. Vaccines need to be given before a child encounters the disease. Waiting until a disease is circulating in the community may not allow for enough time for a vaccine to offer protection.

Vaccines are the best defense against getting vaccine-preventable diseases at a young age when children are more susceptible to serious complications or death from infection. When you delay your child’s vaccines you are increasing the chance they will get sick should the disease enter your community. It is dangerous to keep children from getting their recommended vaccines.

Children under five are at the highest risk from getting sick from disease because their bodies don’t yet have strong defenses to fight deadly infections. If a child is vaccinated according to the recommended schedule, they are protected against 14 serious vaccine-preventable diseases by the time they are two years old.

It’s important to vaccinate children before they become active in the world and encounter disease. By the time an outbreak occurs it may be too late to get vaccinated. Some vaccines need several doses for full protection, and bodies can take days to two weeks to build immunity to a vaccine germ. Don’t wait until it’s too late.

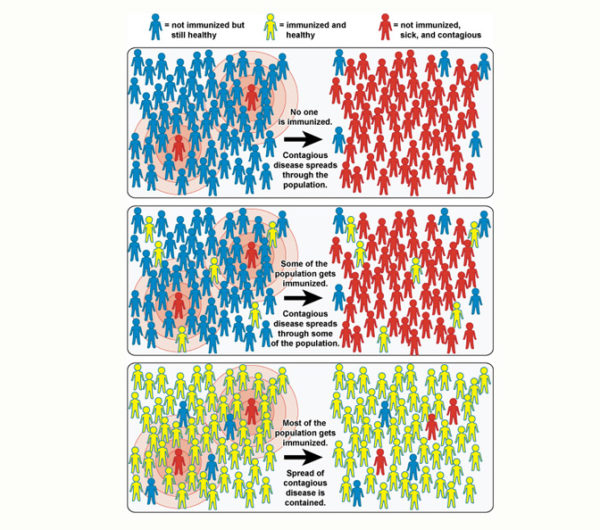

Community immunity (herd immunity) happens when most of the population has immunity to a disease so that the chance of that disease spreading through the community is low. when most of the population is vaccinated, it helps keep everyone safe from disease.

Herd immunity protects all people. Some people are not able to be vaccinated, for example children too young, people with serious allergies against certain vaccine ingredients, people who have not made a strong enough response to the vaccine, and people with weakened or failing immune systems (for example: people undergoing cancer treatment, people with HIV/AIDS, or other health conditions). Those who are unable to get vaccinated are often the ones who are more susceptible to getting very sick from disease. The community can protect those who are vulnerable by getting vaccinated and not letting disease spread.

If a disease enters a community where most people are vaccinated, there’s less of a chance that there will be an outbreak since most people will not get sick and spread it. Not getting vaccinated not only leaves a person open to getting a vaccine-preventable disease but allows for diseases to spread through the community and infect those who might not be able to defend themselves against the disease.

Everyone should be vaccinated according to CDC’s recommended vaccination schedule.

Natural immunity occurs when a person is exposed to a disease, becomes infected, and survives the infection. While it is true that natural immunity usually results in strong defense against future infection, getting vaccinated is much safer than taking the risk of getting sick.

Vaccines teach the body how to defend itself from disease without the risk of getting sick. Sometimes the immune response to the vaccine can mimic mild symptoms of the disease for a few days, but that’s worth it for long-lasting protection from the disease. Infections can have life-long or life-threatening consequences and they’re much more harsh on the body that any possible side effects that could come from a vaccine.

Watch the following video of VYF Board Member, Dr. Paul Offit, as he explains why natural immunity can come at a serious price.

Breastfeeding is one way that immunity is passed on, but even breastfed babies need protection. While breastfeeding infants get some protection from infections like colds, it doesn’t protect the baby from all diseases. Infants and all people need to be vaccinated on time and before being exposed to the disease so that they have the best chance of surviving dangerous vaccine-preventable diseases.

CDC’s recommended vaccination schedules include:

It’s still possible to get sick from a vaccine-preventable disease if a person has been vaccinated. Vaccines do not prevent germs from entering the body; they help minimize sickness or keep you from getting sick. Vaccines are not 100% effective, but many come very close.

For example, our seasonal COVID-19 and flu vaccines contain virus strains that are predicted to be circulating that season, and if you get these vaccines and encounter the virus, you may never get sick. However, the strains can change and are not always what is seen predominately when people get sick. That doesn’t mean that the vaccine doesn’t work. It can still help lower the risk of getting sick or very sick and being hospitalized or dying if the virus strain isn’t the same.

There are also instances where people think a vaccine didn’t work when they get sick after being vaccinated but before the body can make immunity. For example, it takes around two weeks for the body to make antibodies to the flu vaccine. Some people get the flu vaccine and get the flu before the body has had a chance to make antibodies. Or someone will get sick with a similar disease like a cold and mistake it for the flu. These things often lead to claims that the vaccine did not give them protection from the flu when that is not the case.

In some cases, around 2–10% of healthy people fail to make an appropriate amount of antibodies to the vaccine germ to be protected from the disease. This is less common in smaller children. If someone does not respond to the vaccine, and they are exposed to the disease, they could get sick. Sometimes another dose of the vaccine will provide immunity to someone who did not make antibodies the first time.

Should someone get sick with a disease they’ve been vaccinated against, they tend to have a much milder disease than they would have if they did not get vaccinated. Vaccines keep people from getting sick, but they also keep people from getting very sick and being hospitalized or dying should they encounter the disease from their environment.

Lastly, when you get vaccinated and do not get sick, you keep the disease from moving through your community. Getting yourself and your family vaccinated protects others from getting sick, as well.

Read Tim’s story about his daughter Maggie and his son Eli to learn more about the importance of community immunity during an outbreak of measles.

Yes. Infants need to be protected with vaccines from birth according to CDC’s recommended vaccination schedule (birth–6 years). While breastmilk provides great benefits to the child, such as protection from some infections such as colds, it doesn’t protect the baby from all diseases. To be sure your child is protected against vaccine-preventable diseases, follow the schedule from the beginning when the child’s immune system has a harder time fighting off disease.

It’s also safe for the mother to be vaccinated while breastfeeding. Except for smallpox and yellow fever vaccines, vaccines are safe for breastfeeding individuals and their infants. There’s no need to deviate from getting vaccinated just because you’re breastfeeding.

Resources:

Some vaccines need more than one dose for the body to develop proper immunity to the vaccine-preventable disease. This typically depends on how the vaccine is made. Vaccines that contain live, weakened germs cause a much stronger immune response than other vaccines, therefore they require less doses for protection from that disease. Other vaccines may need several doses for lasting immunity.

The MMR vaccine, for example, is a live vaccine and protects against measles, mumps, and rubella. One dose of the vaccine, given at 12–15 months old, offers around 93% protection. The second dose, given between four and six years old, bumps it up to around 97% protection from the diseases. Two doses of MMR offer life-long protection, however there are special circumstances where a booster dose is given.

In contrast, the DTaP vaccine, which protects against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (whooping cough), is given to children at 2 months, 4 months, 6 months, 15–18 months, and 4–6 years. The DTaP vaccine is made with diphtheria and tetanus weakened bacterial toxins, and part of the pertussis bacteria. It’s a weaker vaccine than MMR, and therefore needs more doses for protection. At age 11–12 years, children get a dose of Tdap (the booster for teens, adults, and pregnant people). Adults will get one dose of Tdap, and then a dose of Td (only tetanus and diphtheria) or a Tdap booster every ten years. Pregnant people should get a dose of Tdap every pregnancy because the pertussis element protects babies from whooping cough, and people may be offered a dose in the case they are wounded and need protection from tetanus.

There is a difference in dose between these vaccine types, but if the CDC recommended vaccination schedules are followed as they should be, both vaccines offer great protection against disease.

CDC’s vaccine schedules have been carefully selected for the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines. They’re also closely researched to determine the best timing to give doses for the greatest immunity from disease.