My Polio Story is an Inconvenient Truth to Those Who Refuse Vaccines

by Judith Shaw Beatty

In 1949, the year I was hit by the poliovirus, 42,000 cases of polio were reported in the United States and 2,720 people died, most of them children.

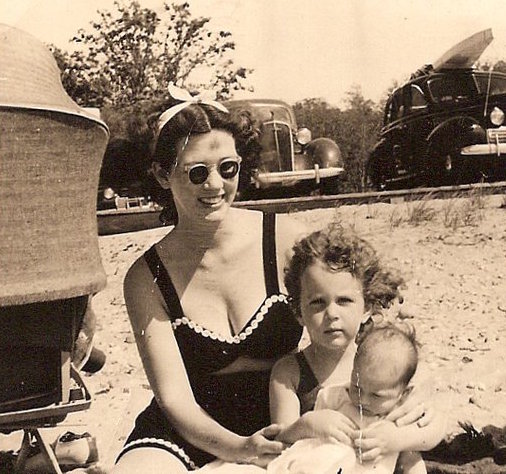

Here I am at the beach with my mom and my sister before I contracted polio.

I was diagnosed with paralytic poliomyelitis, which is experienced in less than 1 percent of poliovirus infections. Not only did it immobilize me completely from the neck down, it also attacked my lungs. It was August, a popular month for polio, and I was six years old.

A few weeks before, my parents, younger sister and I had moved from the outskirts of New York City to Rowayton, Connecticut, which back then was a small town of 1,200 people. My father had gotten a job as associate editor at Collier’s Magazine and my mother was a homemaker, and our new two-story house with its big yard was in sharp contrast to the tiny apartment we had come from.

The poliovirus attacks very quickly.

I was playing with other children at a lawn party and developed such a terrible headache we had to go home. When I woke up the next morning, my legs were so weak I couldn’t stand on them and I could barely lift my arms. It took all day for the doctor to visit the house and examine me, and that night I was taken to the Englewood Hospital in Bridgeport and put in an iron lung.

My mother told me years later that the prognosis was very poor and I was expected to die within hours.

This photo was taken at a garden party, just one month before I contracted polio.

One of the children I was playing with at the party was John Leavitt, who many years later went to work in the field of biotechnology at the Bureau of Biologics of the FDA. Part of his work involved growing live poliovirus, and it was necessary to be tested for polio antibody titre. All those years later, he learned that he must have had the natural polio infection based on the results.

Now, looking back, we realize that while I went home and ended up in an iron lung, John ended up with a flu-like disease with no paralysis. To this day, no one knows why the vast majority of people attacked by the virus recovered with no residual effect and so many others went on to spend the rest of their lives in wheelchairs.

After I was taken to the hospital, the health department put a yellow quarantine sign on the front of our house and at the end of our driveway.

My mother said that when she and Dad would go to the beach in town, people would grab their blankets and umbrellas and move. At the grocery store, my mother said she could hear people whispering and staring. No one wanted to be near my family. Everybody knew of somebody who had died from polio or was crippled by it, and 1949 turned out to be a record year. At its peak in the 1940s and 1950s, polio would paralyze or kill 500,000 people worldwide every year. And there was no vaccine for it, so there was no defense against this invisible, raging monster that struck indiscriminately.

I have no memory of being in the iron lung.

People came to visit me, but I don’t remember any of that. I don’t know how long I was in it, either, but I remember waking up in a bed and looking over and seeing this enormous gray metal cylinder with windows along the sides and wondering what it was. I thought maybe there were tiny people living inside.

During those first few weeks, there were 200 children in my hospital ward with more arriving every day.

Some of the children were toddlers or babies in diapers, paralyzed and crying, and their family members were not allowed near them. There was a lot of commotion and noise. I just lay there, day after day, listening to it. There was chicken wire nailed to the door of my room and it had to be unhooked for someone to come in. I remember my parents coming to visit and leaning over the wire to wave at me, and throwing small gifts that they hoped would land on my bed. They were not permitted to approach me.

There were not enough nurses.

I got very little attention, and when I did, I wasn’t treated very well and my wants and needs were not readily met. I think the nurses must have been going crazy. I remember spilling a bowl of cereal on myself, lying in the wet mess for hours and then being shouted at and shamed by someone very frustrated and upset. I was just getting my strength back, but I was extremely weak and really couldn’t do much. I was given books to read, and with the limited knowledge I had of the alphabet, I taught myself to read and had reached fourth grade reading level when I finally went home. The first book I ever read was “The Sleepy Kitten.”

There was a wringer-washer at the other end of my room next to a big porcelain sink. Twice a day, a nurse would fill the washer tub with steaming hot water and then run cut-up old army blankets through the mangle and wrap them around my arms, legs and midriff. They called them hot packs, and they were painfully uncomfortable. The smell of wet wool is with me to this day and brings up deep emotions. This treatment, which included whirlpool baths, was a clinical method developed and promoted by Australian nurse Sister Elizabeth Kenny, and I believe it saved me from a lifetime of total paralysis.

After a few weeks, both of my arms and my right leg recovered but my left leg did not.

The nurses then told me I would be transferred to another floor in the hospital and that all of my books and toys would have to be incinerated or given to other infected children. I left everything behind when I left that room several weeks later.

This photo was taken on my 7th birthday in October, 1949. I was home on a two-day “furlough” from the hospital.

My new room downstairs had three other children in it. One of them was a young teenager named Lois, and we got to be friends even though she was much older than me. I thought she was very sophisticated. The nurses on this floor were equally overworked and frustrated. None of us could walk, so we were at their mercy and sometimes had to fend for ourselves. This included passing a bedpan around until it was full because we couldn’t get anyone to give us a clean one, and sharing food.

At this stage of my illness, I was allowed to go home on two-day “furloughs” for my birthday and Christmas. When I went home for my seventh birthday in late October, my parents had invited some children my age to help entertain me. It was still warm outside and I lay on a lounge chair and watched the children play tag. The next day, it was back to the hospital for another two months until Christmas.

I was finally discharged in mid January 1950, five months after my diagnosis, and was fitted for a steel and leather leg brace that extended from my ankle up to my hip. I used wooden crutches.

As soon as I was home from the hospital I was sent off to the first grade, which I was utterly unprepared for emotionally, physically, socially and psychologically. I’d already missed the first six months of school, so started off way behind. I had extreme anxiety that would boil over when my mother left my sight because I thought she would never come back. I had a wretched time focusing on anything. I had no idea about asking to go to the restroom and peed in my pants. I didn’t know how to make friends, and clumping around with a heavy steel leg brace and crutches certainly meant I couldn’t play any sports. I used to stand on the playground and watch the other kids jump rope and play hide and seek. I fell dozens of times because I wasn’t coordinated or because the lock on the hinge of my brace would fail. Once, I broke my wrist. I also would sprain my ankle. My right knee, the “good knee,” was a bloody mess sometimes. I coped by developing a rich fantasy world. Sometimes, it caused problems. One time in class, we were given crayons and a picture of a tree to color. I colored the leaves brown and the trunk green, which looked perfectly okay to me but made the teacher mad. I don’t think I learned anything that school year, and in the second grade I had a tutor instead of going to school.

Here I am pictured with my sister Janis in Roxbury, CT when I was just 9 years old.

In the following year, I had my first major surgery, which was at Stamford Hospital in Connecticut.

My ankle was fused to keep my foot stable, and I spent about a month in the hospital. Two years after that, I spent three weeks in Boston Children’s Hospital after they removed the growth platelets from my “good” leg to minimize the difference in leg lengths. By that time, I had severe scoliosis and had been wearing a back brace. Because the back brace was so heavy and bulky, my dresses had to be specially made. I was fitted for my first bra while in the hospital. My mother brought it to me and I tried it on with the sheet pulled over my head for privacy. I also got my first kiss in the hospital, from another patient. It’s amusing to me, oddly enough, that I experienced these rites of passage while hospitalized.

That was the year of the first clinical trial of the Salk vaccine, which was pronounced successful.

I read about it in the newspaper. People stood in line for hours waiting for the shot when it became available in 1955. I didn’t have the vaccine because I was immune. In the years that followed, there were so few polio cases that people only heard about the rare ones that would crop up somewhere in another state, and those stories were so unusual they’d be in the newspaper.

About four years ago, my story was published online and then shared by people on Facebook. I became active in advocating for the importance of vaccines and, for the first time, learned that there were people out there who opposed vaccinations of any kind.

I share my personal story in hopes that it will encourage polio vaccination and support of polio eradication.

I’ve been hearing from them ever since. Either they declare that I never really had polio, or else they insist that polio is still around and has new names because the vaccine was ineffective and that this is part of a cover-up by “big pharma.” Other people, in an effort to shut me up, angrily point out that they know someone who was permanently paralyzed by the polio vaccine or injured by it in some unspecified way, as though that should be a reason for getting rid of the vaccine altogether. Now, these same people are claiming that it was DDT that created the polio epidemics, even though there is evidence that polio existed in ancient Egypt and that more recent epidemics preceded the introduction of DDT.

The lack of compassion expressed by these people is startling. I’ve never interacted with a vaccine refuser who cared one way or the other about my life as a polio survivor. They don’t want to hear about it because I’m an inconvenient truth, just like all the other polio survivors I know. On Facebook, I’m lectured and attacked by arrogant people who claim they know a lot more than I do about polio.

Vaccine preventable diseases like measles, chickenpox and whooping cough are experiencing resurgence all over the U.S.

People who oppose vaccines, who themselves were very likely vaccinated as children but do not extend the same privilege to their own offspring, insist that all disease is caused solely by bad water and poor sanitation. In fact, they will insist there wouldn’t be any disease at all if everyone ate organic food and washed their hands more often, and that polio attacks people in Africa because Africa is unsanitary. Actually, Africa has been polio free for more than a year, thanks to an intense immunization campaign.

I live less than three hours from Colorado, which has the lowest vaccination rate in the country, and in some areas of the state, the immunization rate is lower than in Sub-Saharan Africa. This means that someone flying in from Pakistan or Afghanistan, the only two countries left where polio is still paralyzing and killing people, could theoretically infect children in Colorado were it not for herd immunity. According to the World Health Organization, failure to eradicate polio from these last remaining strongholds could result in as many as 200,000 new cases every year, within 10 years, all over the world.

Recently, someone pointed out to me that natural immunity is preferable to any vaccine at all based on a false belief that disease strengthens the immune system. Vaccine preventable diseases continue to kill millions of people every year around the world. And just speaking personally, yes, I am immune to polio, but the damage it did was hardly worth it.