Are Vaccines Safe?

Understanding Vaccine Safety

The safety of vaccines is taken very seriously. Vaccines are among the most-tested and safest medical products available. It’s normal to have questions about the safety of any food, product, or medicine you and your family use – including vaccines.

Here, we address some of the most common questions about vaccine safety.

This page has been verified for accuracy by a member of VYF’s Committee of Scientific and Medical Advisors, last updated February 2024.

How We Know Vaccines Are Safe

In the U.S. we have a network of safety systems that constantly monitor for safety signals and alert at the slightest detection of a problem.

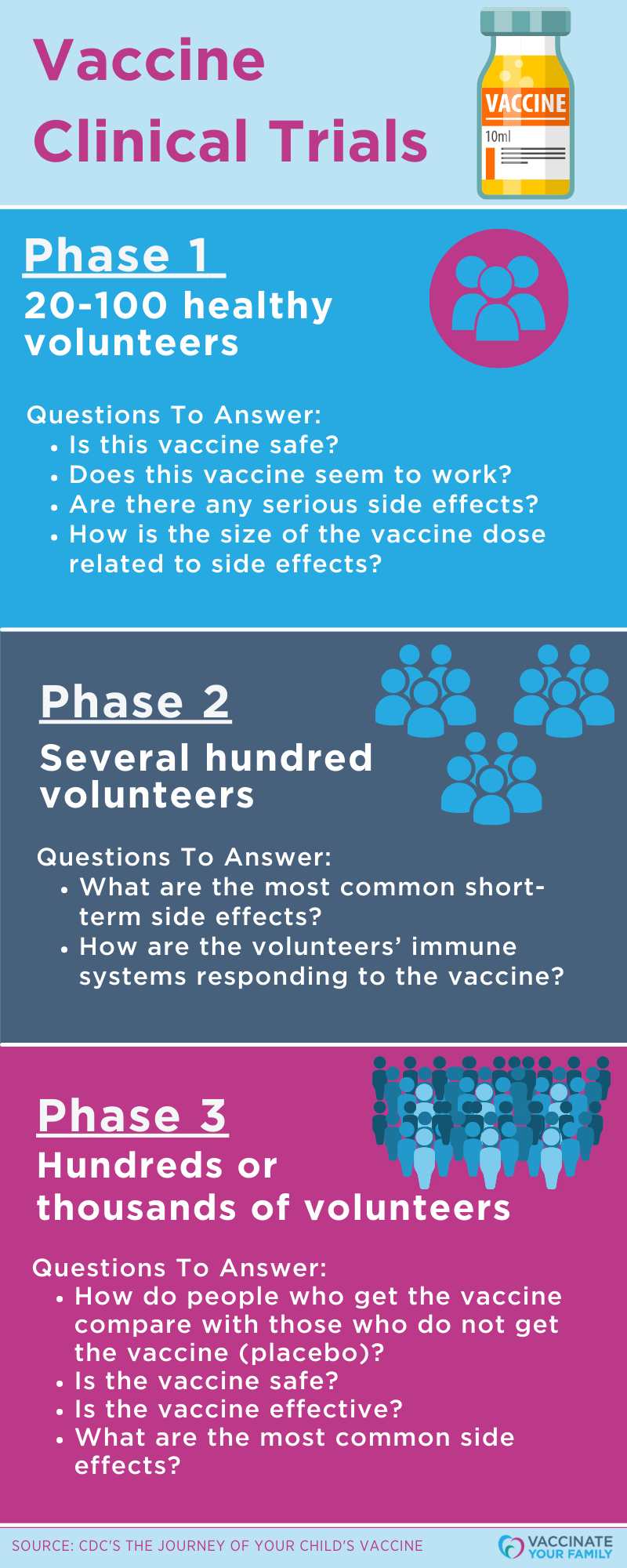

Yes. Before any new vaccine becomes available for use , extensive testing is done in a lab and many clinical trials are conducted to make sure the vaccine is safe and effective. Once there’s enough research, the vaccine is sent for approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). If the FDA licenses a vaccine, it moves to CDC experts to decide if it will be added to the recommended vaccine schedule.

See CDC’s The Journey of Your Child’s Vaccine, an infographic that shows details on how a vaccine moves from development into licensure and beyond.

Even after a vaccine becomes available for use, the vaccine’s safety continues to be monitored so that possible rare risks can be identified. If risks are found, then vaccine recommendations may change to keep people safe. As with any medication, side effects and serious, but rare, reactions can occur. Most side effects are minor and often include soreness or redness at the site where the shot was given and sometimes a low-grade fever.

Find vaccine information by disease on CDC’s Vaccines by Disease web page to find vaccine-specific information on safety. Also see CDC’s Current VISs (Vaccine Information Statement) web page to find information on each vaccine, including safety information.

Resources:

- CDC: Understanding the ACIP and How Vaccine Recommendations are Made in the U.S. (video)

- Add from Video FAQs: Are vaccines safe?

- CDC: Ensuring the Safety of Vaccines in the United States

- CDC: The Journey of Your Child’s Vaccine (Infographic)

- CDC: How Vaccines are Developed and Approved for Use

- CDC: Vaccines by Disease

- CDC: Current VISs – find information on each vaccine

All medications come with potential risks, but the risk of not vaccinating is much greater than any risk of potential harm that could come from a vaccine. Vaccinations are one of the most successful and beneficial public health interventions, right up there with clean drinking water. They reduce the spread of disease and reduce the risk of complications and death from vaccine-preventable diseases.

It’s because of vaccines that many vaccine-preventable diseases are not a threat any longer. However, that doesn’t mean they aren’t still out there. Countries all over the world experience outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, and due to easy travel from country to country, diseases can be brought into unsuspecting communities across the world, including communities in the U.S.

Vaccines are the best defense against getting vaccine-preventable diseases, and they don’t just protect those who are vaccinated. When most of the community is vaccinated, it helps keep everyone safe from disease. Not getting vaccinated not only leaves a person open to getting a vaccine-preventable disease but allows for diseases to spread through the community and infect those who might not be able to overcome the disease.

Risks associated with vaccines are generally mild and thanks to many monitoring systems, vaccines are continuously monitored for safety.

Talk to a healthcare provider before you make any decisions to not vaccinate because it can affect the health of your family and your community.

Resources:

- Vaccinate Your Family: Vaccine Benefits

- Vaccinate Your Family: Vaccines Protect Communities

- CDC: Diseases You Almost Forgot About (Thanks to Vaccines)

- CDC: Who Should Not Get Vaccinated with These Vaccines?

- CDC: Vaccines by Disease

- CDC: Current VISs – find information on each vaccine

No, the flu vaccine can’t cause the flu. Flu shots are made from either flu viruses that have been ‘inactivated’ (killed) or a particle designed to look like the flu virus. Both stimulate the immune system to respond without causing the flu.

While some people may get mild side effects from the flu shot like a sore arm, a headache, muscle aches, or a low fever, the side effects usually disappear after a few days.

Learn more about the current flu season and flu vaccine safety.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) set the recommended immunization schedules in the U.S. based on recommendations from its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The recommended schedules include:

- Children from birth to six years

- Children from 7–18 years

- Adults 19 years and over (including pregnancy)

The ACIP is a group of experts who carefully review all available safety and efficacy data to make vaccine recommendations. The recommendations include when vaccines should be given, the number of doses needed, the timing between vaccine doses, and any precautions and contraindications (situations where the vaccine might be harmful to the patient). The ACIP has three regular meetings every year, in addition to emergency meetings. All meetings are available to the public. See CDC’s ACIP Meeting Information web page for more.

The ACIP recommended vaccination schedules are the only schedules rigorously tested for safety and effectiveness and are updated every year.

The children’s schedules are carefully timed to provide the best protection at the time they are most vulnerable to, and before they are exposed to, vaccine-preventable disease. In addition, the schedules consider the age when the child’s immune system will provide the strongest response.

While some parents may have heard about “alternative” or “non-standard” vaccine schedules, it is important to understand that none of these other vaccination schedules have been tested for their safety and effectiveness, and so they can be dangerous to a child’s health. Speak to a healthcare provider before making decisions that go against medical recommendations.

Before any new vaccine is put on the market, extensive testing is done in a lab and in clinical trial participants. When a new vaccine is developed it must be found safe and effective to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Once the FDA licenses a vaccine, it moves to CDC experts to decide if it will be added to the recommended vaccination schedule.

Following licensure and the addition of the vaccine to the schedule, the vaccine’s safety continues to be monitored so that possible risks can be identified. Since vaccines are held to very high safety standards, if risks are found, then vaccine recommendations may change to keep people safe. As with any medication, side effects can occur, as can serious, but rare, reactions.

There are many monitoring systems in place that help detect vaccine safety issues:

Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) – VAERS is a passive, early warning system that is managed by CDC and FDA and designed to alert both entities to safety issues. Anyone can report an injury, including healthcare professionals, patients, patient representatives, vaccine companies, and others. Since anyone can report their own vaccine issue, VAERS reports cannot be used to determine a link between a side effect and vaccine, however, the information can be used to see if unexpected or unusual patterns emerge that may indicate a safety issue that should be explored further.

Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) – VSD is a collaborative project between CDC’s Immunization Safety Office and healthcare networks and organizations across the United States. This system uses databases of medical records to track the safety of vaccines. Since it uses medical records instead of self-reports like VAERS uses, this system can better help determine if a side effect is linked to a vaccine, especially rare and serious adverse events following vaccination.

Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Project – CISA is a national network of vaccine safety experts from the CDC’s Immunization Safety Office and several medical research centers and partners. This project addresses safety issues, conducts high quality clinical research, and assesses complex clinical adverse events following vaccination. CISA also helps to connect clinicians with experts who can help consult on vaccine safety questions related to individual patients.

Post-Licensure Rapid Immunization Safety Monitoring System (PRISM) – PRISM is a partnership between the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research and health insurance companies. It actively monitors and analyzes data from a representative subset of the general population. PRISM links data from health plans with data from state and city immunization information systems (IIS). PRISM has access to information for over 190 million people allowing it to identify and analyze rare health outcomes that would otherwise be difficult to assess.

Biologics Effectiveness and Safety (BEST) System – BEST system looks at multiple data sources to detect or evaluate adverse events or study specific safety questions.

V-safe – This safety monitoring system was developed for COVID-19 vaccine monitoring but currently monitors how an individual feels after having an RSV vaccine. Individuals who have had an RSV vaccine are able to register for V-safe to receive personalized, confidential health check-ins via text or email to ask how they feel after vaccination. This information helps CDC to monitor vaccine safety and let others know what to expect after getting an RSV vaccine.

COVID-19 vaccines, like all vaccines, are carefully monitored for safety. According to the CDC, COVID-19 vaccines have gone through the most intensive safety monitoring in U.S. history and will continue to be monitored as long as the vaccines are in use.

Resources:

- CDC: Ensuring the Safety of Vaccines in the United States

- CDC: The Journey of Your Child’s Vaccine (infographic)

- Vaccinate Your Family: How Do We Know Vaccines are Safe?

- CHOP: How Are Vaccines Tested Before They Can Be Given to Kids? (video)

A combination vaccine is two or more different vaccines that have been combined into a single shot. With combination vaccines, people get the same protection as they do from individual vaccines but with fewer shots.

Examples of combination vaccines for children in the U.S. include:

- Combination of DTaP, Hepatitis B, and IPV

- Combination of MMR and varicella

- Combination of DTaP and IPV

- Combination of DTaP, IPV, and Hib

- Combination of DTaP, IPV, Hib, and hepatitis B

The MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine, DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis) vaccine for young children, and the Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) vaccine for adolescents and adults, each protect against three diseases, but aren’t called combination vaccines in the U.S. This is because you cannot get separate vaccines for all the diseases that MMR, DTaP, and Tdap protect against.

As with individual vaccines, before a combination vaccine is approved and recommended for use in the U.S., it goes through rigorous testing to make sure it is safe and effective when given with the rest of the recommended vaccine schedule. Just like for individual vaccines, safety systems are in place after the combination vaccines are recommended to the public to watch for side effects.

CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is a group of experts who carefully review all available safety and efficacy data to make vaccine recommendations for the use of vaccines. The recommendations include when vaccines should be given, the number of doses needed, the timing between vaccine doses, and any precautions and contraindications (situations where the vaccine might be harmful to the patient).

The recommendations come from lots of testing and safety and efficacy data that are presented to the committee during meetings when they get together to discuss new information regarding vaccines. The vaccines schedules are carefully timed to provide the best protection at the age when the child’s immune system will provide the strongest response. Since most vaccines need more than one dose for the best protection, all data is analyzed to find the best timing to give the doses and how much vaccine is needed for each age group to produce the strongest response.

During the development of a vaccine, different doses are tested to determine the lowest amount that will be effective for those getting the vaccine. The vaccine dosage is typically set for a certain age range. And some vaccines are only given to certain age groups. For example, DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis) vaccine is given to young children, and Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) vaccine is given to older children, teens, adults, and pregnant women. The number of doses can vary by age, as well, for example, some children (age 6 months–8 years) who have not had the flu vaccine before will need two doses their first year and one dose every year following, while people who have had the vaccine before will only need one dose every year.

Resource:

While vaccine manufacturers do make money from the sale of vaccines, these companies make more money off other medicines and interventions that they produce.

Vaccines are “cost saving” products, meaning that they save the healthcare industry and the country money. For every $1 spent on childhood vaccines, the country saves an estimated $10.90 in healthcare costs due to prevention of disease. Outbreak responses take time, money, and manpower; vaccines save billions of dollars in healthcare costs by preventing outbreaks.

The cost of medical treatment, hospital beds, supplies, doctors, nurses, and everything involved when someone contracts an infectious, vaccine-preventable disease is a much greater expense than that of a vaccine. So, by providing safe and effective vaccines, pharmaceutical companies are not only saving the healthcare system money, but are saving countless numbers of people around the world from unimaginable loss.

As with any medication, vaccines can cause side effects. Most vaccine side effects are mild and go away quickly on their own.

The most common side effects are:

- Pain, swelling, or redness where the shot was given

- Mild fever

- Chills

- Feeling tired

- Headache

- Muscle and joint aches

- Sometimes fainting, which can happen after any medical procedure

Serious side effects are extremely rare and occur around a few minutes to a few hours after vaccination. Serious allergic reactions only occur in about 1–2 out of 1 million doses given.

Signs of a severe allergic reaction can include:

- Difficulty breathing

- Swelling in face or throat

- Fast heartbeat

- Rash all over the body

- Dizziness and weakness

Call 911 or go to the nearest hospital if experiencing a severe allergic reaction to a vaccine.

Parents should pay extra attention to their child’s overall health for several days after vaccination and call a healthcare provider if something is concerning. Report any side effects experienced from vaccination to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), an early warning system that is managed by CDC and FDA that collects reports of vaccine issues.

See the possible side effects from each vaccine on CDC’s Possible Side Effects from Vaccines web page.

Watch this video from CDC to see what to expect when your child gets vaccinated: What to Expect When Your Child is Vaccinated.

If a child or anyone is having a serious reaction to a vaccine, call 911 or take them to the nearest hospital. Also alert the child’s healthcare provider.

Most children do not have serious side effects from vaccines, but vaccines, like other medications, can cause side effects. Most side effects are mild, such as a low-grade fever or soreness at the injection site. If your child experiences a reaction at the vaccine injection site, use a cool, wet cloth to reduce redness, soreness, and swelling. Speak to the child’s healthcare provider about fever/pain reducing medicines.

In very rare cases, a vaccine can cause a serious side effect, such as a severe allergic reaction. Health problems after a vaccine are not always vaccine-related, but if you have concerns, call the healthcare provider.

If a child received a recommended vaccine and is believed to have had a serious reaction as a result, a parent or guardian can file a report in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) so that the event is documented.

Any parent or representative of a child who received a vaccine that is routinely recommended for children and is believed to be injured as a result, can file a petition with the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP). There are no age restrictions.

See a list of CDC’s current vaccine information statements (VIS) that include side effect information for each vaccine.

If an adult or pregnant person is having a serious reaction to a vaccine, call 911 or take them to the nearest hospital and alert their healthcare provider.

Most people do not have serious side effects from vaccines, but vaccines, like other medications, can cause side effects. Serious side effects are extremely rare and occur around a few minutes to a few hours after vaccination. Serious allergic reactions only occur in about 1–2 out of 1 million doses given. Signs of a severe allergic reaction can include difficulty breathing, swelling in face or throat, fast heartbeat, rash all over the body, and dizziness and weakness.

There are some vaccines that should not be given in pregnancy but many are safe and necessary. If a pregnant person is experiencing a serious reaction to a vaccine, they need to get to a hospital or call 911.

Anyone who received a vaccine and experienced a serious reaction should file a report in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) so that the event is documented.

Any adult who received a vaccine that is also routinely recommended for children (i.e. flu, pertussis) and believes they were injured as a result, can file a petition with the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP). There are no age restrictions.

The CDC’s ACIP, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM) recommend flu, whooping cough (Tdap), COVID-19, and RSV vaccines for all pregnant women. These vaccines have been studied and have been shown to be safe for pregnant women and their babies.

See a list of CDC’s current vaccine information statements (VIS) that include side effect information for each vaccine.

Some vaccines use chicken eggs or embryo during the manufacturing process, which means that trace amounts of egg proteins may be found in the final vaccine product. These vaccines include:

- Measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) – grown on chicken fibroblast cells, and contains no egg allergen allergens

- Rabies – can be grown in chick embryo

- Yellow fever – grown in chick embryo

- Flu shot, and the flu nasal spray – most flu vaccines are produced using eggs and may contain trace amount of egg proteins. There are flu vaccines that are not made using egg.

Recent studies show that people with a severe egg allergy can safely receive egg-grown vaccines.

CDC recommends that everyone 6 months and older with an egg allergy receive the annual flu vaccine. The Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters of the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) and the American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI) as well as the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) back this recommendation by stating that no special precautions are required for the administration of influenza vaccine to egg-allergic patients no matter how severe the egg allergy.

Even though it’s considered safe to vaccinate people who have egg allergies with egg-grown vaccines, it’s important to let the healthcare provider know so the vaccine recipient can be watched for rare symptoms of allergic reaction.

Resources:

- AAP’s HealthyChildren.org: Which Flu Vaccine Should Children Get?

- Vaccinate Your Family’s current flu season web page

Hepatitis B vaccines are made using baker’s yeast, which means there can be leftover yeast particles found in the vaccine. The current recommendation is that anyone with a serious allergic reaction to a prior dose of hepatitis B vaccine or to yeast should not get the hepatitis B vaccine. People with mild yeast allergies can get vaccinated.

Many studies show that people with a yeast allergy can safely get vaccinated. For more information, view this fact sheet from CHOP’s Vaccine Education Center.

It is not dangerous to get many vaccines at the same time. Children receive many vaccines at a young age so that they are immune to vaccine-preventable diseases before they are exposed to them. When vaccines are delayed or spread out, this will leave a child unprotected as protection against the disease will be delayed.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) set the recommended immunization schedules in the U.S. based on recommendations from its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). The ACIP is a group of experts who carefully review all available safety and efficacy data to make vaccine recommendations for the use of vaccines. Based on extensive research, recommendations include which vaccines are safe to be given at the same time.

Since many vaccines are recommended in the first few years of life, to reduce the number of shots a child receives some vaccines are offered as combination vaccines. A combination vaccine is two or more different vaccines that have been combined into a single shot. With combination vaccines, people get the same protection as they do from individual vaccines but with fewer shots.

Although there seem to be more vaccines given at one time, there are significantly less antigens in vaccines for children today. Antigens are the substances from the germs that trigger the immune system to develop antibodies. Thirty years ago, children were only vaccinated against 8 diseases, and the total number of antigens was a little more than 3,000. Today, by age two, children are recommended to get vaccines that protect against 14 diseases, but the total number of antigens in these vaccines is only around 300. This means that vaccines are much safer than ever before.

The antigens in vaccines are very minimal compared to what a child encounters every day. A healthy baby’s immune system can’t be overloaded by many vaccines at once. With combination vaccines and giving multiple vaccines at once, the number of office visits is decreased, as is the amount of stress on the child and parents.

A number of studies show that getting several vaccines at the same time is safe and does not cause any chronic health problems. The recommended vaccines have been shown to be as effective in combination as they are individually. Sometimes, certain combinations of vaccines given together can cause fever, and occasionally febrile seizures occur because of the fever. Febrile seizures are temporary and do not cause any lasting damage. Febrile seizures can also occur when a child has a fever from an illness. Based on this information, both the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommend getting all childhood vaccines according to the schedule.

Resources:

Vaccines will not overload a healthy baby’s immune system, in fact, vaccines strengthen the immune system. Babies are born with immune systems that are already able to fight off many germs, however, their immune systems are not well-equipped to fight off infections from vaccine-preventable diseases. For their bodies to fight off these deadly diseases, they need the help of vaccines.

Children are exposed to thousands of different germs every day in their environment. Even if a baby receives many vaccines in one day, they contain only a fraction of antigens (substances from the germs that trigger the immune system to develop antibodies) that your baby encounters every day. Infants are fully capable of developing immune responses to multiple vaccines at the same time, in addition to responding to the many other challenges present in the environment.

Thirty years ago, children were only vaccinated against 8 diseases and the total number of antigens was a little more than 3,000. Today, by the age of two, children receive vaccines that protect against 14 diseases, but the total number of antigens in these vaccines is only around 300. Now vaccines protect children’s bodies against many more of these germs because of the immunity provided by the vaccines.

Resources:

It is safe for children to receive extra doses of vaccines. If a child received a vaccine before it was recommended, there’s a chance that he or she was not old enough to make proper immunity to the vaccine. For example, MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine given before 12 months of age may not give a baby long-lasting immunity from all three diseases.

If a vaccine is not given at the minimum intervals listed on the recommended immunization schedules then the vaccines might not be as effective. The recommendations include when vaccines should be given, the number of doses needed, and the timing between vaccine doses. If a child has missed a dose or will be getting a dose later than the schedule recommends, the healthcare provider will often continue vaccinating according to schedule.

If a childcare center or school has determined that a child needs additional vaccines because they were not vaccinated according to the schedule or according to state laws, it’s because they are trying to be certain that diseases do not circulate the classrooms to spread to others.

Be sure to talk to your child’s healthcare provider to be sure he or she is being immunized on schedule.

Children can still get vaccinated if they have a mild illness like a cold, cough, ear infection, mild diarrhea, and/or low-grade fever if the temperature is less than 101º. Experts at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) agree that children with mild illnesses can still get vaccines, as there are no health benefits to delaying them.

Vaccines do not make symptoms of an illness worse, even though they may cause mild side effects like a low fever, or soreness or swelling where the vaccine(s) was given. It is also fine for a child to get vaccinated if he or she is taking antibiotics for a mild illness. Antibiotics won’t affect how the body responds to the vaccines. So don’t delay. It’s very important for children get their vaccines on time to help protect them as soon as possible from serious diseases.

Your child’s healthcare provider can help best determine if the child should be vaccinated as planned, or if the appointment needs to wait.

It is not safe to alter the recommended vaccine schedule to delay vaccinations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) set the recommended immunization schedules in the U.S. based on recommendations from its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The recommended schedules include:

- Children from birth to six years

- Children from 7–18 years

- Adults 19 years and over (including pregnancy)

The ACIP is a group of experts who carefully reviews all available safety and efficacy data to make vaccine recommendations for the use of vaccines. The recommendations include when vaccines should be given, the number of doses needed, the timing between vaccine doses, and any precautions and contraindications (situations where the vaccine might be harmful to the patient).

While some parents may think using about “alternative” or “non-standard” vaccine schedules, it is important to understand that none of these other vaccination schedules have been tested for their safety and effectiveness, and so they can be dangerous to a child’s health. Speak to a healthcare provider before making decisions that go against medical recommendations.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), preterm infants are at increased risk of experiencing complications from vaccine-preventable diseases but are less likely to receive immunizations on time. Preterm infants should be given every vaccine according to the recommended childhood vaccine schedule just like full term babies.

The AAP states that parents of preterm babies who are concerned about vaccinating should keep the following issues in mind:

- If preterm babies get the infections that vaccines can prevent, they have a greater chance of having disease-related complications

- Vaccines are safe when given to preterm and low birth weight babies

- Any side effects associated with vaccines are similar in both full-term and preterm babies

Children are exposed to diseases everywhere they go. Vaccines need to be given before a child encounters the disease. Waiting until a disease is circulating in the community will not allow for enough time for a vaccine to offer protection.

Vaccines are the best defense against getting vaccine-preventable diseases at a young age when children are susceptible to serious complications or death from infection. Delaying a child’s vaccines increases the chance that he or she will get sick should the disease enter the community. It is dangerous to keep children from getting their recommended vaccines.

Children under five are at the highest risk from getting sick from disease because their bodies don’t have enough defenses to fight deadly infections. If a child is vaccinated according to the recommended schedule, they are protected against 14 serious vaccine-preventable diseases by the time they are two years old.

Infants need to be protected with vaccines from birth according to CDC’s recommended vaccination schedule. While breastmilk provides great benefits to the child, such as protection from some infections such as colds, it doesn’t protect the baby from all diseases. Babies have not yet been exposed to infectious diseases at birth, which puts them at greater risk for infections. Even though the baby can get some short-term protection from the mother, to be sure a child is protected against vaccine-preventable, infectious diseases, follow the schedule from the beginning because it takes time for a very young child to build immunity to fight off vaccine preventable diseases.

There are many systems in place that continuously monitor vaccine safety and effectiveness. Vaccinate Your Family has collected these studies so that the public has easy access. Learn more about the science behind the safety and efficacy of vaccines by visiting our Vaccine Research section.

Also see AAP’s HealthyChildren.org Vaccine Safety: Examine the Evidence web page.

The internet can make finding great research easy and fast, however between all the great research is a lot of false and misleading information. If you aren’t well versed in reading medical and scientific journals, then it’s important to learn how to find sources of credible and accurate information and how to weed out information that’s incorrect.

Just because the media is promoting research, or the information is on an organization’s website, doesn’t always mean that it’s credible or valid. When reading a study or information online ask these critical questions:

Who is reporting the results and through what publication(s)?

The information should be coming from a credible source like a government entity and should be updated on a regular basis to include new information. Web content should be well-researched, well-written, and approved by subject matter experts like medical professionals. Scientific research should be peer reviewed, which means that the research has been reviewed by members of the same profession in the relevant field to account for the author’s credibility.

In general, sites that have credible information are federal government agencies, medical schools, and large professional or nonprofit organizations.

What is the site’s purpose?

Many websites have an “about us” page where it will explain the site’s purpose. This may give you an idea if the site has biases that may indicate there’s an opinion that is skewing the information.

How is the website funded?

The source of funding should be listed on the website and can show the reader a lot about the intent of the site’s information. If a website looks like it has a lot of ads, it may not be a reputable site.

Are you looking for information that backs up what you already believe to be true?

Conformation bias is the tendency to look for information that supports already formed beliefs. Searching for information just to confirm what you already believe isn’t choosing to search for information that may be accurate. Accurate information is what we know to be scientific fact. People who want to be accurate accept the facts no matter if it goes against their beliefs. People who want to be correct look for information to support their opinions even if it goes against what experts state to be true.

Did the researcher in the study analyze animals or people?

Animal testing may be a good indicator of how a medical intervention or drug could act in or on a human, but conclusions cannot be drawn from animal research. There are differences between animals and humans, so until a human study is done, a researcher cannot be sure that the same results of the animal studies will be achieved in humans. Clinical trials show how well a medical intervention or drug works in people.

Who are the people (subjects) that were observed in the study?

Some studies are limited to a particular/specific group of people, for example, men with diabetes or children under four with asthma. In studies where there is a specific group of people, there are limitations on how conclusions can be drawn about the general population. Pay attention to the group of people being studied.

Was the study a randomized controlled trial?

Randomized controlled trials (RCT) look for effectiveness of new medicines. In RCTs, the people participating in the study are randomly divided into either the experimental group or the control or comparison (given a conventional treatment) group. The researchers are looking to see if the participants in the experimental group who got the new treatment have a different outcome than those who either received a placebo/no treatment or a conventional treatment.

RCTs help to remove bias from the experiments because the two participant groups are put together at random.

“Good” science follows a set of rules and guidelines called the “scientific method.” To conduct good science using the scientific method, the researcher must:

- Ask a question

- Research credible, science-based sources to find out what may already be known about the topic

- Develop a testable hypothesis – a proposed explanation or theory based on limited evidence as a starting point for further study. Sometimes people refer to the hypothesis as “an educated guess.”

- Do an experiment or study to determine if the results support the hypothesis

- Analyze the data from the experiment and draw a conclusion regarding the hypothesis that was tested

- If the study does not support the hypothesis, the researcher should decide whether to create a new hypothesis

- If the study supports the hypothesis, the researcher should communicate the study’s results to others

Even though scientists set out to conduct research based on data, sometimes human emotion, error, and biases gets in the way. For example, a researcher may:

- Discredit or overemphasize an observation in the study

- Take shortcuts instead of using proper study methods

- Create a weak test of the hypothesis

- Include opinions into the study observations and treat them as fact

- Start with a conclusion instead of a hypothesis and then design a study around coming to that conclusion

One of the most important parts of research is to publish the study so that other researchers can try to reproduce and test the findings. When others can duplicate a study’s findings using the same method, that helps to show that the original study’s results are valid.

When communicating the results from a study or discussing a theory, a good researcher should share all information, not just information that is positive to the study. Positive, negative, and neutral results are all important in communicating research to help others in furthering research down the road.

There are not studies where people are purposely not vaccinated with approved vaccines in order to compare them to vaccinated people. Since vaccines work, scientists would not leave people exposed to vaccine-preventable diseases by not vaccinating them because that would not be ethical.

There is no need to do these kinds of studies because vaccines are among the most rigorously tested and safest medical products on the market. Vaccines typically take around a decade or more to move from the lab into the arms of the public. Evidence of safety is gathered for as long as a vaccine is in use.

There are some studies that have looked at the differences in health between children who have been vaccinated and children who have been left unvaccinated. One such study, Vaccination Status and Health in Children and Adolescents, found that allergic disease and non-specific infections did not depend on vaccination status. Meaning, children who were vaccinated were no more likely to get colds, allergies, ear infections, and other non-vaccine preventable diseases any more so than children who are not vaccinated.

Resources

- AAP’s HealthyChildren.org: Vaccine Safety: Examine the Evidence

- Vaccinate Your Family: Vaccine Research

Vaccines and their ingredients do not cause autism. Many studies (find links to studies here) have been conducted that have found there is no connection between vaccines and autism. However, many people claim that vaccines do cause autism largely based on a fabricated study.

The discredited study, citing a link between the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine, thimerosal, and autism, was published in 1998 by Andrew Wakefield and 12 colleagues. This team studied a small sample of 12 children. No other team could replicate the Wakefield’s results. Not long after, 10 of his 12 colleagues came out with a retraction to the paper saying there was no link between autism and vaccines. This was accompanied by allegations of ethical violations and misconduct by the Wakefield team. His entire publication was retracted, Wakefield was charged with fraud, and his medical license was revoked.

Despite the paper’s retraction and centuries of research, some people still believe that autism can be caused by vaccines, particularly thimerosal-containing vaccines. Even though studies show that thimerosal is not harmful, as a precaution, in 2001 thimerosal was removed from the vaccines in the childhood vaccine schedule. There is no link between other ingredients in vaccines to autism.

Parents can be confident that the medical community endorses the childhood schedule, and the vaccines are continuously monitored for safety. See the evidence by reading the many studies that show no link between vaccinations and autism.

For more information, visit Autism Science Foundation’s Autism and Vaccines web page, or download the Truth About Autism and Vaccines guide created with ASF.

See these important videos about vaccines and autism:

The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) is a government-funded payout program for people who claim to be injured by vaccines. The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (also referred to as “the vaccine court”), housed in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, initiated the Omnibus Autism Proceedings (OAP) in July 2002 to consolidate the thousands of claims filed by petitioners claiming that vaccines caused autism. The petitioners’ lawyers formed a Petitioners’ Steering Committee (PSC) in order to consolidate the processes and, in conjunction with the Court, decided that all the cases filed fell within three theories:

- MMR vaccine and other thimerosal-containing vaccines combined cause autism

- Thimerosal-containing vaccines cause autism

- MMR vaccine causes autism

The overall decision was that MMR vaccine and other thimerosal-containing vaccines combined do not cause autism. Decisions include:

- Cedillo Decision – Special Master Hastings

- Hazlehurst Decision – Special Master Campbell-Smith

- Snyder Decision – Special Master Vowell

The overall decision was that thimerosal-containing vaccines do not contribute to autism. Decisions include:

- Snyder Decision– Special Master Sweeney

- Dwyer Decision– Special Master Vowell

- King Decision– Special Master Hastings

Only the first two cases were heard. The third was deemed to be too similar to the others to justify an additional hearing.

Resources

- United States Court of Federal Claims: Docket of Omnibus Autism Proceeding

- HRSA: National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program

The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP), sometimes known as the “vaccine court,” was created in 1986 as a no-fault, government-funded payout program for people who claim to be injured by vaccines. This program is funded by a small tax put on each vaccine.

A $0.75 excise tax is put on each dose of vaccine for every disease that is prevented. So, vaccines like HPV and flu are charged a single $0.75 tax because they each prevent against a single disease, and vaccines like MMR and DTaP are charged a $2.25 tax because each of the vaccines prevent against three separate diseases.

The Department of Treasury collects the taxes and manages the funds which are paid out to people needing compensation. By using these funds and not litigating with the vaccine manufactures directly, vaccine costs and supply can remain stable so that people are able to continue to have access to lifesaving vaccines.

If someone believes they were injured by a covered vaccine, they can file a petition. Parents and legal representatives can file on behalf of children, disabled adults, and individuals who are deceased. People who believe they were injured by a COVID-19 vaccine can file for benefits through the Countermeasures Injury Compensation Program.

Find the most recently updated payout data report at the top of the Vaccine Injury Compensation Data web page.

When someone is awarded compensation for a vaccine-related injury that does not mean that the vaccine caused the alleged injury. Around 60% of compensation awarded by National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) is due to a negotiated settlement that the has not come from a concluded vaccine injury. This is often due to a desire to minimize time and expense of litigating a case.

One of the most common claims is a condition called Shoulder Injury Related to Vaccine Administration (SIRVA) which occurs when the vaccine is administered in the shoulder but not in the correct place. This is an injection site error by the person who administered the vaccine and not an injury due to the vaccine itself.

Vaccines are safe and injury from the vaccine is rare, but recipients can be covered by these programs should injury occur.

Find the most recently updated payout data report at the top of the Vaccine Injury Compensation Data web page.

A law called the Vaccine Act was passed in 1986 to protect vaccine manufacturers from civil personal injury and wrongful death lawsuits resulting from vaccine injuries. While vaccines can cause rare serious side effects and death (like from a serious allergic reaction), litigation is complex because of the challenge to show cause and effect for vaccine injury.

That being said, there are two federal government programs that compensate people with vaccine-related injuries:

- National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP): People claiming vaccine injuries don’t have to prove that the vaccine caused damage, they only have to show that the injury occurred within a time period after the vaccine was administered

- Countermeasures Injury Compensation Program (CICP): This program addresses public health emergencies and national security threats such as the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccines, medications, or devices used to prevent or treat a public health emergency

Resource:

- Find Law: Can I Sue Vaccine Manufacturers?